Perpetual Timelapse wasn’t my first big programming project, but it was the first that wasn’t bound by the Scratch

scratch.mit.eduScratch - Imagine, Program, ShareScratch is a free programming language and online community where you can create your own interactive stories, games, and animations.

canvas or the screen of my calculator

cemetech.net Pi_Runner's contributions | Archives | Cemetech. I started development just before the beginning of 2020, and the resulting system uploaded daily time-lapses to YouTube

YouTubePerpetual TimelapseNOTE: Unfortunately, the system is not currently in operation, with no plans to resume it in the future. The gaps...

canvas or the screen of my calculator

cemetech.net Pi_Runner's contributions | Archives | Cemetech. I started development just before the beginning of 2020, and the resulting system uploaded daily time-lapses to YouTube

YouTubePerpetual TimelapseNOTE: Unfortunately, the system is not currently in operation, with no plans to resume it in the future. The gaps...

on most days from April 9th to June 1st, 2020. During this time, the system processed and uploaded over 16 hours of video, representing over 660 hours of time-lapse recording. Although the final iteration of the system took longer than expected to develop and presented reliability issues, I gained valuable programming/integration experience and increased confidence in my abilities to tackle complex problems.

on most days from April 9th to June 1st, 2020. During this time, the system processed and uploaded over 16 hours of video, representing over 660 hours of time-lapse recording. Although the final iteration of the system took longer than expected to develop and presented reliability issues, I gained valuable programming/integration experience and increased confidence in my abilities to tackle complex problems.

Inspiration

In late 2019, I was interested in filming time-lapses, mainly of the clouds and weather throughout the day. I also wanted get my hands dirty with a “real” programming language, so I set a goal to create a system that could film daily time-lapse videos and upload them to YouTube, all with no (or very minimal) human input.

By searching on YouTube, I had seen a few channels that were similar to my vision: daily time-lapses from sunrise to sunset. Some of them had fancy auto-generated thumbnails and descriptions, and sometimes even music, so these became additional features that I wanted to implement eventually. Examples of these channels that I saw (and sometimes even communicated with the creators of) were Daily Timelapses

YouTubeDaily TimelapsesPlease support our channel by subscribing! This way you can enjoy beautiful relaxing soothing daily time lapses with hand-picked musicSo...

, Time Lapse

YouTubeTime LapseDaily TimeLapse from Majadahonda on Madrid

, Time Lapse

YouTubeTime LapseDaily TimeLapse from Majadahonda on Madrid

, and Tigh Ban Lek

YouTubeTigh Ban LekTigh Ban Lek holiday Cottage is a stunning modern cottage which offers comfort and luxury combined with spectacular views. The...

, and Tigh Ban Lek

YouTubeTigh Ban LekTigh Ban Lek holiday Cottage is a stunning modern cottage which offers comfort and luxury combined with spectacular views. The...

. It’s clear that these channels aren’t motivated by views (they often have 10 times more videos than subscribers), but I find it strangely soothing to watch a day passing in a place that I’ve never been and just watch the clouds drift over the landscape.

. It’s clear that these channels aren’t motivated by views (they often have 10 times more videos than subscribers), but I find it strangely soothing to watch a day passing in a place that I’ve never been and just watch the clouds drift over the landscape.

Anyways, that’s how, on December 25th, 2019, I set out to build this system. Not only that, but I wanted to start uploading on the new year, only a week later. That may seem overly ambitious (and it was), but I actually did manage to get some sort of system set up by then. It was the iteration process on that initial system that extended the project into a months-long endeavor that persisted into the 2020 quarantine.

Process

I chose to use Python for the project, mainly because of its reputation for being powerful and easy to learn. Since I hadn’t written in Python before, there was a learning curve, but as the project progressed it became easier to work with as I learned the basic features of the language.

Initial Version (Phone)

My first plan involved controlling a phone programmatically to take individual time-lapse frames and transfer them to the computer during daylight hours. Then, they would be combined into the final video and uploaded, ideally during the night.

So, I started by making a program to repeatedly call Android Debug Bridge to trigger the shutter on the phone and transfer each frame to the computer. Then, when the day’s frames had been captured, FFmpeg

ffmpeg.orgFFmpeg was used to create a video from the frames, and the video was uploaded with the YouTube API (though I used a script called youtube-upload

GitHubGitHub - tokland/youtube-upload: Upload videos to Youtube from the command lineUpload videos to Youtube from the command line. Contribute to tokland/youtube-upload development by creating an account on GitHub.

since I had no experience with APIs at the time).

since I had no experience with APIs at the time).

This version of the system was ready by New Year’s 2020, but I had only been able to test it over short durations up to that point. When it came time to film the time-lapse for January 1st, the problems with the initial setup became apparent:

- The phone would overheat from being in the sunny window

- The phone would randomly disconnect from the computer

- The phone would periodically lose focus, even though it was set to infinite

As it turns out, a phone is not built for taking thousands of photos while continuously connected to a computer and baking in the sun. After this realization, I spent a couple months testing and honing the other parts of the system while using an old webcam to take the actual frames. At this point, I probably could have just bought a nicer webcam and called it a day, but I was hesitant to spend money on the project.

Improved Version (GoPro)

Luckily, I remembered that I had an old GoPro that could be used instead. I had previously disregarded that idea since I didn’t think it would be possible to control the GoPro or transfer the footage to a computer without human intervention. When I further researched the topic, though, I found that the GoPro WiFi commands

GitHubGitHub - KonradIT/goprowifihack: Unofficial GoPro WiFi API Documentation - HTTP GET requests...Unofficial GoPro WiFi API Documentation - HTTP GET requests for commands, status, livestreaming and media query. - GitHub - KonradIT/goprowifihack:...

had been documented by the legendary KonradIT

GitHubKonradIT - OverviewMessing with grounded and airborne cameras. KonradIT has 71 repositories available. Follow their code on GitHub.

had been documented by the legendary KonradIT

GitHubKonradIT - OverviewMessing with grounded and airborne cameras. KonradIT has 71 repositories available. Follow their code on GitHub.

![]() , meaning that it might indeed be possible to use the GoPro. Another advantage to this approach is that I could use its built-in time-lapse feature, eliminating the need to combine the frames on the computer.

, meaning that it might indeed be possible to use the GoPro. Another advantage to this approach is that I could use its built-in time-lapse feature, eliminating the need to combine the frames on the computer.

However, there were still major challenges to overcome, namely staying connected to the GoPro’s WiFi network and transferring multiple gigabytes of video over it every day. Thanks to the goprocam

GitHubGitHub - KonradIT/gopro-py-api: Unofficial GoPro API Library for Python - connect to...Unofficial GoPro API Library for Python - connect to GoPro via WiFi. - GitHub - KonradIT/gopro-py-api: Unofficial GoPro API Library...

Python module, I could easily send commands to the GoPro, but it took a lot of trial and error before I could reliably keep the WiFi network alive so that the time-lapse could be started at dawn and ended at dusk.

Python module, I could easily send commands to the GoPro, but it took a lot of trial and error before I could reliably keep the WiFi network alive so that the time-lapse could be started at dawn and ended at dusk.

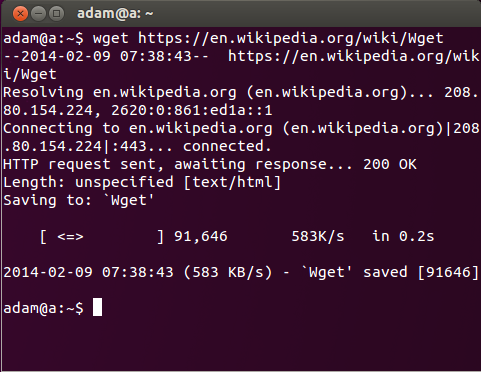

Then, I had to figure out how to download the video, which typically came in the form of multiple video segments topping out at 4GB each. In the end, this involved querying video metadata through the WiFi commands before downloading each segment with a fine-tuned Wget

en.wikipedia.orgWget - Wikipedia

command. These steps worked most of the time, but because the GoPro couldn’t record and transfer files at the same time, the video had to be completely downloaded overnight, or else the system would fall behind. As you might imagine, this tended to happen frequently due to the fragile nature of the whole setup.

command. These steps worked most of the time, but because the GoPro couldn’t record and transfer files at the same time, the video had to be completely downloaded overnight, or else the system would fall behind. As you might imagine, this tended to happen frequently due to the fragile nature of the whole setup.

Reliability issues notwithstanding, the new setup using the GoPro is the one that ran from April to June 2020. But what happened to the videos after they had been transferred?

Video Creation and Packaging

With the day’s time-lapse video downloaded to the computer, the program made three different versions at different speeds (short, medium, and long), again using FFmpeg. Then, a thumbnail was generated programmatically using ImageMagick

ImageMagickImageMagickCreate, Edit, Compose, or Convert Digital Images

, and songs were selected from a hand-picked royalty-free music library to fit the length of the video. As time progressed, I also started added more fun metadata to the video description, and towards the end even made a system to detect “good” sunsets/sunrises and upload separate videos for those.

, and songs were selected from a hand-picked royalty-free music library to fit the length of the video. As time progressed, I also started added more fun metadata to the video description, and towards the end even made a system to detect “good” sunsets/sunrises and upload separate videos for those.

With the videos processed and ready to go, they would then be uploaded to YouTube, likely during the morning hours as the next day’s time-lapse had already started. At least, if everything had gone according to plan.

Lessons

The lessons that I learned from this endeavor boil down to two main ideas:

- Ability to change directions from initial plans

- Self-reliance and confidence in problem solving (given enough time)

First, I was stuck for a while as I tried to make my original idea work. But when I took the time to assess all of my available resources, that opened up more possible ways to solve the problem. Then, I could evaluate the tradeoffs between these different approaches to find the most practical solution. Today, I like this “backtracking” aspect of problem solving because it often leads to surprising methods to overcome or circumnavigate roadblocks in the development process.

Which leads to the second point: that working on this project fueled my self-reliance and confidence that I could solve any problem (within reason), at least given enough time. On one hand, this has been a motivating factor in all of my personal projects since. If I have a vision that seems out of reach at first, but I can break it into manageable pieces and solve each of those, then I can compose them into something awesome. However, that last part, time, is something that I’m still improving on today. I’ve gotten much better at giving myself reasonable deadlines and limiting scope if necessary, but sometimes it can still be a challenge, especially when working in unfamiliar territory.

As a whole, I’m still proud of this project, and of myself for making the jump into “real” programming that led to where I am today.